Dream Vessels: Creating Peace in Troubled World

Artist Marsha Connell watched preparations for the first Persian Gulf War from the bottom of a hill. The view that appeared in a dream began a healing process that ultimately brought her peace.

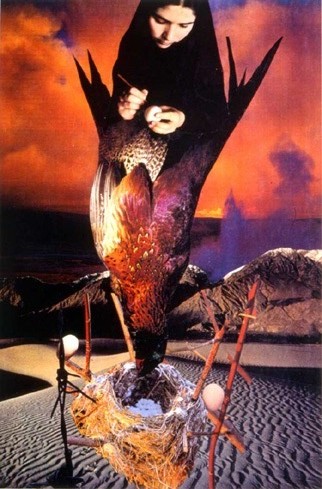

Collages, dark landscapes spiked with light, became her way to communicate. “I felt a distress so profound there were no words for it,” Connell says. She calls the collages “Dream Vessels” because each dreamlike picture contains a vessel — a pot, a vase, a ship.

A month after the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in August 1990, Connell dreamt women writers, artists, and poets were brought in to observe the fighting.

A friend suggested the dream meant the artist was to bear witness. Before this dream, Connell felt artists lacked power to elicit change. Then she wondered, “Could I create art about the war, but not beautify the destruction?”

Connell cut up magazines, made two collages and duplicated them on a color copier. When she looked at the copies, she says, “They shocked me. They moved me so much. There was alot of darkness but also hope. They had hope for the world.”

One collage, “Mayam,” is a kaleidoscope of red, glowing smoke, dark rocks jutting from the ocean, and the sedentary head of her teacher Maya, who committed suicide. More rocks and shattered pots loom. Behind the smoke emanates light.

Reba, Connell’s daughter who was spending her junior year in Israel when the Gulf War erupted, was the original recipient of the collages. Since Israel was under missile attack, the war posed a double agony for Connell as she worried about her daughter’s safety and the future of the world.

Connell made dozens more prints, which she sent to Reba, who hung them on her dormitory walls in Jerusalem.

The series led to a show of Connell’s collage prints at the Bade Museum in Berkeley, California in 1993. A limited edition book of selected collages and poems accompanied the show. Connell made another three dozen collages that led to more shows and appearances and a video for cable television.

Before the burgeoning interest in her collages, Connell, who also teaches art at a local Junior College, was known for her watercolors which are in private collections throughout the Bay Area.

For Connell, vessels hold personal, political, and spiritual significance. Like the white, translucent oriental vase adorned with roses filling the center of the collage “Witness,” as a young girl, Connell often felt fragile. Her mother’s name is Rose.

In 1989, Connell traveled to Ecuador on a cultural exchange to meet the women of a small village who made pottery. She was driving through the mountains when a car crashed into hers, shattering the pots she was going to exhibit in the United States. Connell created a collage which conveys her feelings of loss and then restoration.

She finished the original series with a collage called “The Whole World Is a Very Narrow Bridge.” She fears crossing bridges and when she made the collage the world filled her with the same terror. But she points to a verse from the song, “The Whole World” as her newly acquired axiom ….the whole world is a very narrow bridge and the important thing is not to be afraid.

That collage was transitional. Connell has created dozens of collages, markedly different from the earlier ones. Instead of fiery reds and dark hues, in some watery greens and blues prevail. And eggs, the spiritual symbol of wholeness — birth, rebirth — are a central and recurring theme.

In her poem, “Dream Vessels,” Connell writes: “The vessel offers the possibility of transformation, hope/reconciliation of opposites…Vessels poise/between her story and history, bridging nature and the human-made, bridging hope and forces of destruction.”

“Somehow, through doing this, I felt I was finding a way to bring hope together with the darkness,” she reveals. “As the work told me its stories, it was bringing more sense to the world. The collages were my healing. Gradually, I found my own center again and my own peace through doing this.”

(by Joyce Lynn from her article, which first appeared May 6, 1993, in the Santa Rosa (California) Press Democrat)